A few weeks ago, I facilitated a workshop that included a number of neurodiverse writers who were featuring neurodiverse characters. Each of the pieces of writing were in their early stages, but with solid bones. As readers, we were excited to see them develop into fully realised pieces.

Occasionally, when the motivations or actions of characters were queried, the answer was because of the character’s neurodiversity. We accepted this response without further probing and moved on with the session.

Afterwards, this stuck in my mind. It wasn’t just one author giving this explanation – and indeed other authors in other workshops have likewise uttered this. Explaining some quirk of the narrative ‘because the character is neurodiverse’. Something about this explanation irks me. Not because characters can’t be neurodiverse, but because that sentence was being used to explain so much while saying so little.

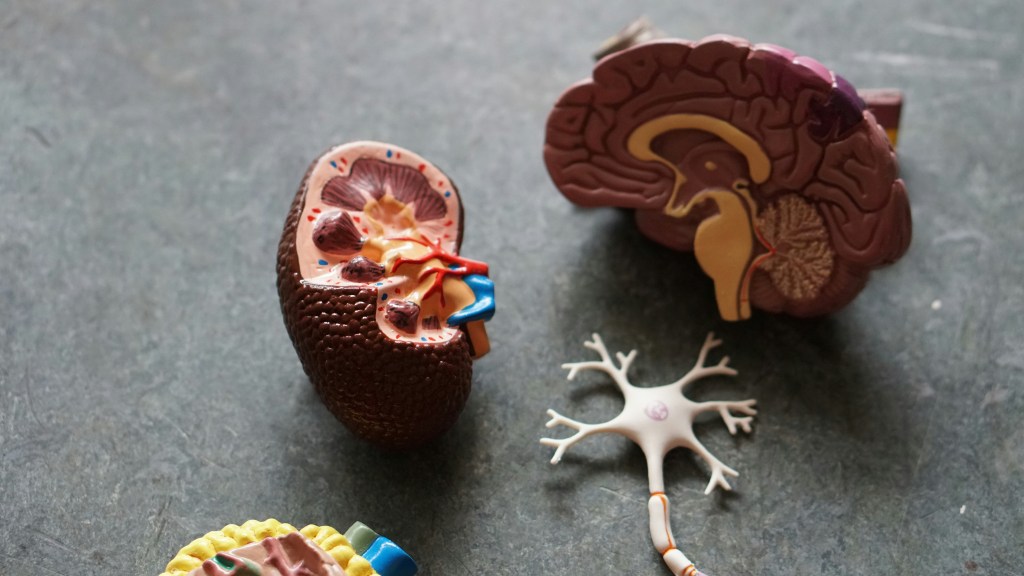

Neurodiversity is a very large umbrella term that is still undergoing a lot of research. At the moment, media focus is on undiagnosed autism and ADHD in adults. But it also covers dyslexia and dyspraxia. There are still others that are only just being defined as differences in brain make up and thought patterns. As people are realising that their struggles are shared by others, communities are being established to support each other. Through this movement, representation of these conditions are increasing in media, including in written stories.

- My own journey

- What does ‘Diagnose your Darlings’ mean?

- Where would I begin?

- Setting up your future self

- The writing will become richer for it

- Legitimising an excuse

- Crafting the perfect narrative

- Overview

My own journey

In the past few years, I’ve come to the realisation that I am probably autistic. This is peer-reviewed by friends who, when I suggested I might be autistic, were surprised that I’m not already formally diagnosed. In addition, I have been formally diagnosed with many of the comorbidities of autism without the overarching umbrella.

When I was 16, I was diagnosed with Obscure Auditory Disorder – which is now known as Auditory Processing Disorder. I had also lived with Sensory Processing Disorder my entire life without knowing it wasn’t a common experience. I thought it was normal to avoid touching lots of common textures because they made my teeth buzz. I also have special interests. Grammar, writing theory, and story structure are the ones that are central to my life. Most recently I’ve had to come to terms with the probability that I have Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria. This is one I particularly struggle with as it sometimes feels like I’m fighting my own brain.

But I have to remember that while all of these conditions and ‘disorders’ explain some of my experiences, I am none of them, and none of them are me. I am not limited to their existence, and they don’t explain away the decisions I’ve made with my life. They merely connect me with others, allowing me to find the words to describe how I think. Labels – particularly medical labels – can be scary sometimes. But they don’t have to be.

The other side of this is that to be diagnosed is to be privileged in it’s own right. Doors open with a formal diagnosis, in accessing support and legitimising your experience. It’s so expensive and exclusive to get diagnosed. I don’t have the means to pursue it formally. So, I am limited to my own research and the opinions of those who know me best.

My experiences are my own. This bingo card of comorbidities is specific to me. The way my conditions affect me will be totally different to the next person with the same label. I would love to see these differences reflected in the media I consume.

So, accurate representations of neurodiversity are something that’s already on my radar.

What does ‘Diagnose your Darlings’ mean?

Neurodiversity comes with many different, weird comorbidities. They are indicators of the behaviour of people who share these umbrella terms, but aren’t the neurodiversity itself. For example, people with autism often suffer from insomnia. People with ADHD often experience learning differences. People with dyslexia often manifest speech impediments. People with dyspraxia often struggle with light sensitivity.

The number one comorbidity of all neurodiversity is anxiety. Which makes sense when you consider all the hoops someone with neurodiversity has to leap through to live a seemingly ‘normal’ life.

When we’re writing, we often project our own struggles and frustrations with daily life onto the narrative. We change the character’s environment into what we wish we saw in real life. For example, if a writer struggles with Facial Emotion Recognition, maybe they write an alien species that displays no emotions. Or we play out what we wish we could do about our experiences in a controlled, fictional space. It could be as simple as giving a character the kind and supportive friendship group that we wish we had.

I would love to see writers (including myself) thinking about which comorbidities their character might have. Depending on the flavour of neurodiversity, there are a number of ‘character quirks’ which are medically diagnosable differences. And those manifest differently for everyone. There isn’t a blanket experience for any type of neurodiversity. For every person who hates loud noises, there are those who revel in turning the volume all the way up.

Where would I begin?

To start with, I would find a list of common comorbidities for the neurodiversity I wish to represent, and think about which make sense for my character. I wouldn’t choose all, just a few. Once I’ve done this, I would figure out what each comorbidity means for that character’s motivations and actions. Being thorough but not excessive. I don’t want to create a character so rigid in attributes that they become impossible to write into fiction. Likewise, if there’s a stereotype, I’d think about how to break that down or move away from it.

To reinforce this textual research, I would also seek out the lived experiences of others. It would be so easy to make every neurodiverse character I write be a carbon copy of myself. But that isn’t how neurodiversity works. None of us are the same, our experiences aren’t blanket, and our reactions to them aren’t stamps. It’s almost like we are [gasp] people!

Once the story is written, the best cherry on top would be sensitivity readers. They are worth their weight in gold! I even had one for this article. You may find a suitable sensitivity reader among your friends, or you can find them online. They will see things that you don’t and help you fill gaps in your understanding.

The reasons for this are threefold.

Setting up your future self

Imagine it’s 10 years in the future. You’ve been published and your book was an instant overnight success (this is a Dream, after all). Now, you’ve been invited to appear on a panel of writers for a Q&A and a fan steps up to the mic to ask a question about your novel;

“Hi thank you for your writing. It changed my life. Just one question; when the dragon attacks the town, the main character stops and puts her hands over her ears instead of running away like the other villagers. Why does that happen?”

What would you prefer to answer that question with?

- Option 1: “Oh it’s because she’s neurodiverse.” [Next question]

- Option 2: “Oh that’s because the main character is autistic, and she has Auditory Processing disorder. She reacts to sudden, loud noises by being overwhelmed. When the dragon first appears, it roars, which makes her freeze instead of flee. You can also see this reaction further into the story when…” [etc]

The second not only sounds richer, but also promotes awareness of how exactly neurodiversity can affect everyday life. We often forget, as people living with neurodiversity, exactly how we adapt until we are challenged on it by others. We might not try clothes on in shops because we don’t like touching too many different fabrics in a day. We may avoid reading out loud because our dyslexia would make it too frustrating. We may set alarms to make sure we’re eating and drinking when hyperfocusing. These actions are normal and logical to us – but could be completely bizarre to anyone for whom they aren’t routine.

The writing will become richer for it

Taking a closer look at the intricacies of your character’s identity will begin to guide your narrative. In knowing how they react or avoid certain things, you will be able to tell when they are acting within their personality – or when they are actively fighting against it.

As writers we know that the most important element of a character’s development is their motivation. It’s what makes them do what they’re doing, and it pushes both them and the narrative along. It’s the keystone of the entire text. As the author, you need clarity in what affects and guides the way your character expresses that motivation.

To reiterate one of my earlier points, it’s important that you don’t over ‘diagnose’. Not only is this disingenuous to the natural progression of writing, it also could give a prescriptive stereotype of neurodiversity. There have been plenty of poor examples of neurodiversity written by trope-chasing creatives in recent media. They often do more harm than good.

Defining the subtext struggles that your character faces – not just the angst that you’re about to put them through, but the simple ones that we face in our own real lives – will add a layer of deeper meaning to your writing. The summit of the narrative will be that much more fraught, and the payoff that much more intense. Your characters could even try to use their ‘disabilities’ as an advantage. Something I strive to do for myself in reality.

Legitimising an excuse

The simplest and most compelling reason to undertake this extra wealth of research has nothing to do with our writing. It is to do with the space we take up in the community as writers. We can set the standard of what is required and acceptable when being represent people and communities in media.

When you give the explanation of ‘because neurodiversity’ without any deeper connection, you indicate that this is a reasonable response.

It becomes a catch-all to any situation that an author hasn’t thought through. Imagine that same scenario I mentioned above but where the author hadn’t actually realised the minor plot hole? When they’re challenged on it, they could response with the first answer, phrased in exactly the same way. Yet it has a completely different intention.

As readers, we’ve seen plenty of big authors use marginalised people’s experiences as off-the-cuff excuses only when questioned directly. It can be used as a scapegoat for poor, lazy writing. Which is exactly what we don’t want to support or promote.

Crafting the perfect narrative

Neurodiversity is moving away from being associated with a weak retort for the ‘bad parenting’ of naughty 7-year-old boys. It is gaining recognition as something that affects us in ways that have never been considered.

I grew up in one of the households where autism was brushed off as ‘over diagnosed’. Looking back, I realise I was displaying some of the most obvious signifiers of the condition from a young age. But because I was “high functioning” and able to mask, I did so. Unlearning the processes I developed to protect myself – and realising how many I’d put into practice in the first place – has been a wild ride in the past four years.

We’re just beginning to understand what neurodiversity means in our society – in education, in workspace, and in media. As writers of stories, we hold a unique ability to present the true inner processes of a character’s mind. No other artform delves as deeply or as clearly as fiction writing.

We are in the perfect place as writers to shift the narrative of neurodiversity. We can shape something positive in the eyes of our wider audience. Personally, I’d prefer that our differences in mental processes aren’t used as a scapegoat for weak writing. In my own writing, I want to contribute to a world where differences are represented with researched and well-rounded characters. I wish to cultivate a deeper understanding of the daily experiences neurodiverse people live.

I hope that this resonates with you too.

Overview

So, you’re writing a neurodiverse character? Have you done these things;

- Researched the neurodiversity

- Researched the comorbidities of that neurodiversity

- Thought about the impact these comorbidites have on your character

- Made sure the character isn’t a self-insert

- Listened to lived experiences of people with that neurodiversity

- Asked someone with experience of that neurodiversity to read your work

Cover photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Leave a comment